Retiring Professor Feels Gratitude Toward EIU and Community

Aug-01-2005Much to his mother's chagrin, Alan Baharlou often ran around as a youngster with holes in his pants pockets - the result of his carrying rocks and other sharp items of nature that he found while exploring nearby river beds.

"I was always discovering things," he said. "I loved the different colors and shapes. And being in nature brought me tranquility; it gave me peace. It was my friend."

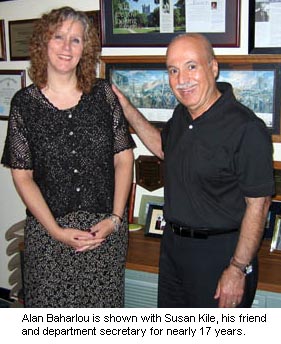

More than five decades have since passed, and the years have provided the 69-year-old Charleston resident more friends than he could ever count. Many of them - while happy for his good fortune - reluctantly said goodbye as the long-time chair of Eastern Illinois University 's geology-geography department prepared for his retirement.

"It was the most difficult decision I have ever made," he said. "I cried when I wrote the letter to Mary Anne (Hanner, dean of the College of Sciences ) and Blair (Lord, provost/vice president for academic affairs). I still get emotional just thinking about it."

"It was the most difficult decision I have ever made," he said. "I cried when I wrote the letter to Mary Anne (Hanner, dean of the College of Sciences ) and Blair (Lord, provost/vice president for academic affairs). I still get emotional just thinking about it."

Friday, July 29, marked the end of Baharlou's 25-year tenure at his beloved EIU. He spent much of the day, as well as the weeks before, packing up and clearing out the third-floor office he had occupied -- as department chair -- for the past 20 years.

A bookcase full of books remained behind. "I'm leaving those for John (Stimac, the new acting chair)," Baharlou said. "He can keep them or get rid of them, however he sees fit."

Gone for good, however, will be the personal family photos, plaques and other memorabilia Baharlou collected over the years. "That is something John will have to build and shape himself, based on his own life's journey," Baharlou said quietly.

Many of the items Baharlou carefully packed represented his time at Eastern - awards, certificates, photographs. . . One black-and-while print -- dated 1958 -- stood out among the rest.

"That is me, receiving my degree from the University of Tehran. It was presented to me by the then-Shah of Iran. I graduated as valedictorian. And that's what made it possible for me to come to the United States."

Even today, more than 45 years later, Baharlou struggles with his emotions as he recalls the circumstances which brought him to his adopted country. He refers to his homeland as Persia, although many years ago the country's name was changed to Iran. And he remembers the desperation he once felt, thinking he'd never escape from the dictatorship that would control who - or what - he would become.

"From childhood, a person was cultivated to follow that line of thinking," Baharlou said. "After awhile, many persons just gave up. They'd get up, walk, eat, sleep - do the things the government told them they were supposed to.

"They were unbearable circumstances if you wanted more," he added.

Baharlou recalled listening to Voice of America, an international broadcasting service funded by the U.S. government.

"This was 10 years before I came to the United States ," he said. "I had access to a short-wave radio and would listen every night. And I would think, How could they do it? How could these Americans protest against the president and live to see the next day?'

"It amazed me that their destinies were in their own hands."

In contrast, Baharlou recalled then-U.S. Vice President Richard Nixon visiting the Persian capital. His motorcade passed by the University of Tehran where Baharlou was in attendance.

"It happened as I was in a large geology class," he said. "Three soldiers came in and randomly shot and killed three of my fellow students. I remember seeing the brain matter left on the floor and wall.

"We were warned that the same thing would happen to us if any one of us demonstrated during the vice president's visit."

As he was growing up, Baharlou realized two things: "I had potential, and I had hope," he said. He studied hard and passed the required entrance exam needed to attend his university.

Much to his delight, subsequent exams helped get him placed in courses in the physical sciences and, more specifically, in the field of geology.

The payoff came when he was named valedictorian of his college - the highest honor a student could achieve. His government traditionally honored such success with the opportunity to study abroad.

"I talked to the Shah twice," Baharlou said. "I reminded him that his father sent students to Europe so they could study, learn and come back to help their own people. I told him I requested the same sort of opportunity."

With his request granted, Baharlou headed for the United States. He enrolled in the University of Oklahoma and soon realized he could never go back to his homeland.

"According to the rules, I had to go back. I was prohibited from so many things, including marrying anyone from the United States ," he recalled. "I sent a letter for permission to stay, but was told, in effect, that my scholarship had been discontinued."

Baharlou acknowledged his fear for the future but said that "everything worked out somehow." Hard work; the support of his wife, Carlene; friends and a little luck helped the determined young scholar succeed.

"It's been a rewarding experience," he said, recalling the past 45 years since he arrived in the states. "I've seen what it's like not to be free and I've learned to take advantage of what freedom offers me.

"But a person has to work a lot harder to function in freedom," he continued. "A person can't be complacent. He must ask questions. He must express himself. He must vote and effectively participate in the democratic process."

Baharlou quickly admits that his own life experience impacts his method of teaching. Yes, he says, his students are there to learn about geology. But seldom does a person leave his classroom at the end of a semester without having "shared some authentic life experiences" that can't help but have an effect on the student as a whole.

For example. "I get some students who come in who are very bigoted, very prejudiced," he said. "My job is to teach them compassion and tolerance by setting an example."

Before his departure, Baharlou's office walls revealed the history of his accomplishments. He received many prestigious awards over the years, such as being named the university's Professor Laureate and recipient of the Ringenberg, Paul Overton and Dean's awards. He was selected as "The Faculty of the Year" by students from 12 Illinois public universities and as "Man of the Year" by EIU's Daily Eastern News, the student newspaper.

But his memorabilia also included a picture frame displaying a glass-protected hand-written note. He explained that the grandmother of one of his students sent it to him after having met and talked with him on a visit. After reading it, he displayed it on his wall as a constant reminder of his duty to his students.

" I am a survivor of a concentration camp. Gas chambers built by learned engineers. Children poisoned by educated physicians. Infants killed by trained nurses. Women and babies shot and killed by high school and college graduates. So I'm suspicious of education. My request is: help your students to be human. Your efforts must never produce learned monsters, skilled psychopaths or educated Eichmanns. Reading and writing and spelling and history and arithmetic are only important if they serve to make our students human ."

"Working at this university is the greatest honor and profession anyone could ever have," Baharlou continued. "As teachers, we invent the future through our students' academic and personal growth. There are student torches to be lighted, and at the end of a semester, I can see my impact.

"I hope, that in some way, my efforts have helped pay back all the things this country and this university have given me."